Using AI to give legal information: Comparing ChatGPT to JusticeBot

Hannes Westermann – Lead Researcher of the JusticeBot project (Cyberjustice Laboratory) and PhD Candidate (Université de Montréal)

Introduction

ChatGPT, the new language model launched by OpenAI in November 2022, has captured the attention of the public and media alike. It is part of a class of increasingly powerful models known as large language models (LLMs), that are able to accomplish many different tasks. People have been able to use such models to accomplish a huge variety of tasks, including writing and explaining computer code,[1] writing short stories[2] and poetry,[3] drafting emails,[4] translating texts[5] and even emulating old computer systems.[6]

In March 2023, GPT-4 was launched, an even more powerful model, which can produce even more sophisticated texts, and analyze images. When given questions from the American bar exam, GPT-4 supposedly achieved a score that would put it in the top 10% of students.[7] OpenAI is also not the only company building these kinds of models – for example, both Microsoft[8] and Google[9] are exploring integrating similar language models in their search engines, to provide more relevant and personalized results.

Of course, the interest in using such models in the legal domain is very high.[10] The legal domain is to a large extent based around text, which is well-suited to applying such models. A number of startups and research projects are aiming to explore how ChatGPT and co can be used in the legal domain. An interesting question is whether ChatGPT may be able to give answers to provide legal information to individuals, which could play an important role in increasing access to justice, as people would be able to ask their legal questions and receive information about their rights. At the same time, as we will explore, exposing language models such as ChatGPT directly to layperson users may not be the right approach, due to potential risks with hallucinated answers.

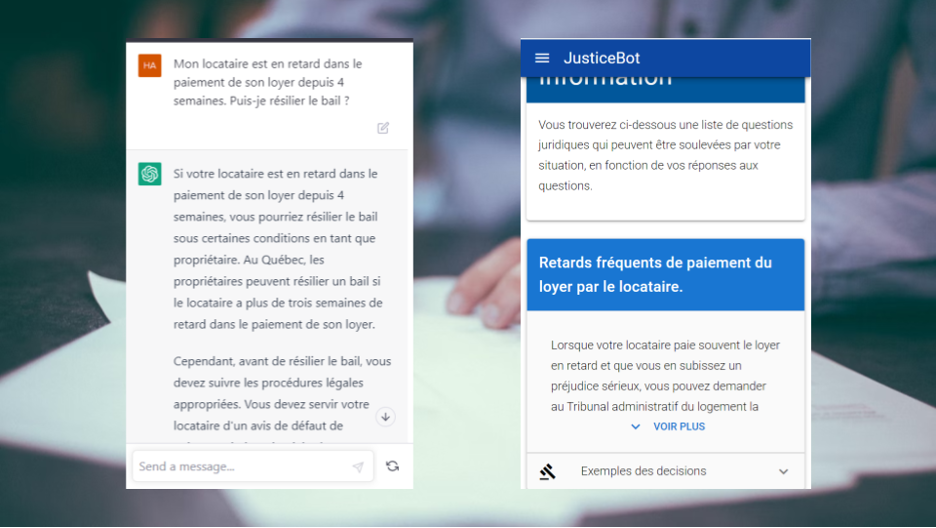

At the Cyberjustice Laboratory, we have developed our own toolchain to give legal information to individuals, called the JusticeBot framework. The tool asks questions of the user, and then provides them with legal information. Currently, we have published a tool using this methodology which focuses on landlord-tenant disputes in Quebec, available at https://justicebot.ca. The tool has been accessed over 18k times, and 89% of individuals responding to a survey about their experience indicate that they would recommend the tool to their friends.

While both JusticeBot and ChatGPT are in theory able to provide legal information, the way they go about this is very different. The JusticeBot methodology relies on legal guided pathways to capture the situation of the user and provide them with legal information and similar cases. ChatGPT, on the other hand, uses a sophisticated neural network to predict the next word in a sequence, to accomplish many different tasks.

In this blog post, I will explore the differences between these approaches. I will start with a brief technical overview of the different methodologies, and then discuss different trade-offs between the different methods.

The technical background

First, let us take a look at the different technologies that underlie ChatGPT and JusticeBot.

JusticeBot

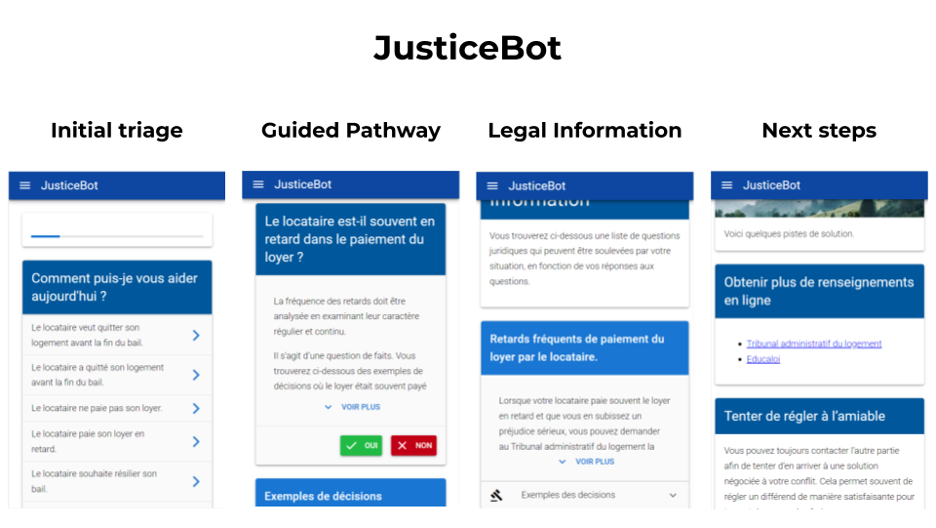

JusticeBot adopts the methodology of an expert system. Using a custom creation tool, called the JusticeCreator, legal experts can encode the logical criteria that judges apply in coming to decisions in certain legal areas. Further, they can add previous judicial decisions to the pathway, that can illustrate how individual legal criteria were previously applied by judges, and the outcome that certain cases tend to lead to.

The user interacts with the system by answering questions, that take them through the legal guided pathway. For each question, they are given a simplified explanation written by the expert, as well as legal cases that can help them understand their situation. Once there are no more questions, they are shown legal information corresponding to the answers they gave, as well as a list of previous similar cases and their outcomes. Further, they are given a list of possible next steps that they can undertake to resolve their issue.

The user can benefit from this information in making a better decision, such as whether to hire a lawyer and/or take their case to court, or even use the information to come to an amicable agreement with the other party. Ideally, the JusticeBot approach can thus help individuals resolve their dispute and contribute to well-being in society.

The approach described above was taken for a number of reasons in the JusticeBot. First, it means that the output of the system is always in full control of the creator, who can decide exactly which information the user will see. The legal expert can thus verify that the information is correct and not harmful to the user of the system, and adapt it to their level of legal understanding.

Second, the system never tries to predict the particular situation of the user – rather, it aims to provide them with general legal information and references to previous cases. The user themselves has to decide how they believe the individual criteria apply to their situation, aided by the context presented. The system also does not attempt to tell the user what they should do, but instead aims to present them with information and a list of potential options, that can help the user decide how to proceed. The fact that the system works this way is made very clear to the user, to prevent them from overestimating the capacity of the system. Further, since the system only gives general information, it is unlikely to run afoul of the rules around the unauthorized practice of law.

The JusticeBot thus provides a way to build tools that are able to support the user better understand their situation and legal rights, in a simple and accessible manner. It thus has the potential to increase access to legal information and access to justice, and to contribute to more disputes being resolved.

ChatGPT

ChatGPT works in a very different way. The model is based on an enormous neural network, that has been trained on billions of pieces of text. Based on reading this text, the model has learnt to predict the next word in a sequence, similar to how phone keyboards can predict the next word we may want to type.

Based on this simple principle, the model has learned sophisticated patterns in text. By giving so-called prompts to the system, it is able to carry out a huge number of tasks. Further, the newest models have been fine-tuned on examples of desirable human interactions, which makes it very easy to ask the model to do things, and have it respond in a useful way.[11] The potential contained in the models such as ChatGPT and GPT-4 are still being explored. For a more in-depth overview of the technical aspects of the models, you can read a previous blogpost by Tan Jinzhe.[12]

ChatGPT can be accessed directly via a free user interface at https://chat.openai.com. The system can also be integrated into other applications through a so-called API (Application Programmatic Interface). In this way, the tremendous abilities of the model can be used to enhance other apps. Each use of the API costs a bit of money, usually less than one cent.[13] For example, one could imagine a “legal information” chatbot, which can answer people’s legal questions. Many people expect models such as ChatGPT and GPT-4 to have a significant impact on many professions – a report by Goldman Sachs estimates that 300 million jobs could be affected by automation.[14]

One potential issue of the current models is that they sometimes tend to “hallucinate”, i.e. fabricate responses that sound plausible. Therefore, for factual questions, it may not be wise to fully rely on the response given by ChatGPT. Instead, it may be more useful to think of ChatGPT as a calculator for words, that can take texts as inputs, and perform some tasks on these texts to generate a relevant output.[15]

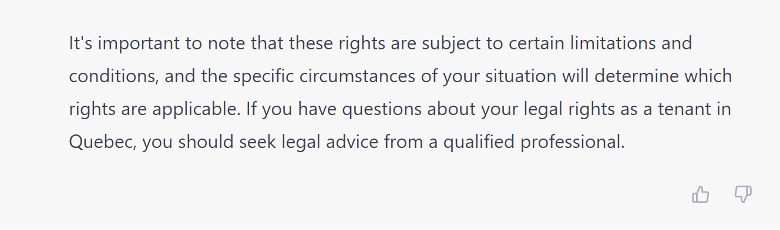

It should be noted that OpenAI is aware of these properties of the model, and their potential risks in the legal domain. As such, the usage policies of the OpenAI models explicitly restrict the use of the models to offer tailored legal advice without a qualified person reviewing the outputs.[16] Further, when asked legal questions, the model will often respond that it is not able to perform legal tasks, and that each case is unique.

Comparison – JusticeBot & ChatGPT

Now that we have compared the technical aspects of ChatGPT and JusticeBot, let us compare the implications of these differences for providing legal information.

Accuracy of information

First, let us consider the differences in the accuracy of the information provided by the system. In the JusticeBot, all of the information has been explicitly encoded by a legal expert, by reading legislation, case law and legal doctrine. The information provided by the JusticeBot is thus deterministic, and can be fully controlled by the legal expert. As long as the interpretation of the legal expert is correct, the user will be provided with accurate information.

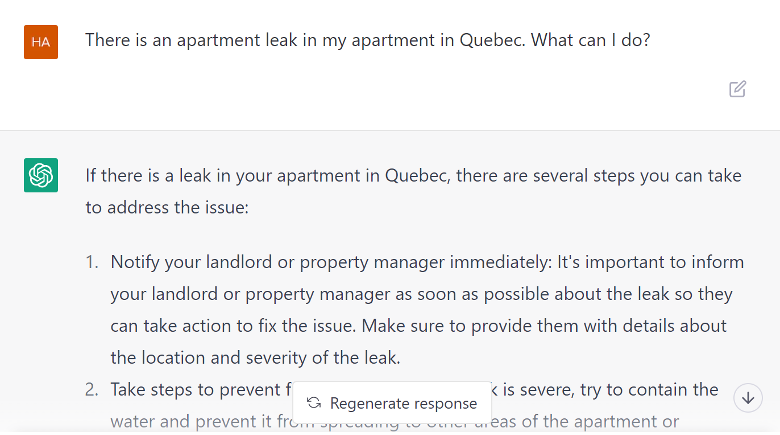

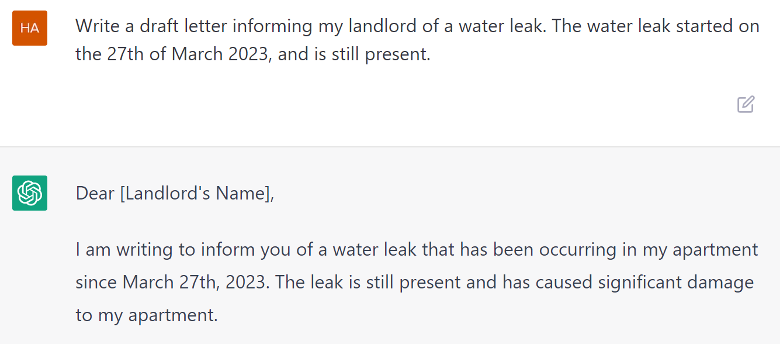

ChatGPT works according to a different principle. When asking the system a question, such as “There is a water leak in my apartment. What are my rights?”, the system will aim to write a plausible answer to this question. As discussed above, sometimes this answer may be a hallucination, and make up legal rights or sources. To counteract this, ChatGPT will often clarify that each situation is unique and that the user should speak to a professional. GPT-4 also hallucinate less than ChatGPT.[17] However, even so, there is a risk of information provided by ChatGPT being incorrect. This degree of incertitude may be acceptable when such a tool is used by lawyers, but may be risky if exposed directly to end-users, who may not have the legal acumen to evaluate the information. This is reflected in the usage policies of OpenAIs models.

We are currently performing an experiment to assess the differences between the information given by ChatGPT and the JusticeBot. Another blog post will be published shortly presenting the results of this study.

Manual work required for creation

In building each new JusticeBot system, a legal expert needs to review the legal area and encode it in the JusticeCreator. The system is built in a way to make this entering of information as simple as possible, and supports the legal expert using e.g. machine learning approaches to surface relevant case law. However, there is still quite a lot of manual work involved in encoding the information into the system.

ChatGPT, on the other hand, theoretically requires no manual work to provide legal information in a new legal area. By being trained on billions of documents on the internet, the system may have come across legal information relating to a specific topic, and be able to find this information and explain it to the user. However, of course, the issue of hallucination remains – the information that is surfaced may or may not be accurate, which can be an issue for certain use-cases.

Scope of information

Each JusticeBot is built to cover a specific legal domain, as encoded by the legal expert creator of the system. The first version focuses on landlord-tenant disputes, while further versions are under development for other legal areas. Within each legal area, the legal pathways covering specific legal questions also have to be encoded by the legal expert. This means that the system to some extent knows when a question is out of scope – for example, if the user selects “other” when asked which issue they are facing, the system informs them that it currently does not cover their question, and therefore cannot help the user. This is an important feature of the system, since it acts as a safety valve that prevents the user from obtaining irrelevant or incorrect information.

ChatGPT, on the other hand, is not constrained by encoded information – since it has access to a lot of the internet, it is likely to have already absorbed a lot of information from different legal domains, as described above. However, ChatGPT does not have the same capability to determine when it does not know enough legal information about a legal area to respond – instead, it may hallucinate an incorrect answer.

Different use-cases

The current version of the JusticeBot focuses on providing legal information to laypeople. The scope is deliberately kept narrowly to provide legal information, both for practical reasons and in order to avoid issues with the unauthorized practice of law. However, we are investigating further versions of the JusticeBot that can expand the approach to support lawyers or judges, generate documents, or take a more active role in dispute resolution.

One of the greatest strengths of ChatGPT is its flexibility. Depending on the question asked, the system is able to provide information, summarize cases, write draft documents or letters, or even generate arguments for or against certain interpretations of the law. This variety of possible tasks makes it an excellent tool for legal experts, who may benefit from the system to generate first drafts of different types of documents, or explore arguments around a legal question. At the same time, fully benefiting from this flexibility requires having legal education, since the responses may contain hallucinated parts that need to be adjusted. Thus, such a system may currently be most useful when used by legal professionals.

Ease of interaction

The JusticeBot provides the user with the ability to explore the relevant information around their own case. They do this by selecting answers to questions about their case, supported by case law summaries. Then, they are given simplified legal information, previous case law encoded in the system and possible next steps. The interaction is designed in a way to be as simple as possible, as the user only needs to click the relevant answers to provide information about their case.

This JusticeBot methodology relies on the user to assess whether legal criteria apply to their case (aided by case law summaries) and how to proceed with provided the information. The system never tells the user what to do, or how to proceed. This, of course, requires some effort on behalf of the user, to themselves decide how their situation may be seen in the light of legal criteria, and how to proceed. Designing the system in this way is a conscious choice – predicting new cases is difficult, and even lawyers may not always know what a court will decide. Further, it reduces issues relating to the unauthorized practice of law, since the system does not give an opinion on a legal matter.

ChatGPT allows the user to interact with it using their own words. The user can write questions that the system answers autonomously. This is a very easy and natural way of interacting with an AI system, as the user is able to ask natural questions and even follow up on previous questions. That said, for some types of information it may require the user to know which questions to ask.

Further, the system is able to perform certain reasoning steps for the user, such as suggesting whether a certain legal criterion applies to the case of the user or not. Of course, such prediction of legal outcomes is inherently risky – what happens, for example, if the prediction is wrong? OpenAI seems to have acknowledged this risk in training the model, which will often highlight the fact that each case is unique and it is not able to predict individual legal cases. Additionally, the use of the models to directly provide tailored legal advice is explicitly prohibited by the usage policies of OpenAI.

Conclusion

We have compared a few aspects of using the JusticeBot approach and ChatGPT to give legal information. Both approaches have different tradeoffs. The JusticeBot is able to give legal information based on pathways encoded by legal experts. While this does take some work, the creator of such a system can be sure that the system will not show misleading information to the user. Due to how the system is designed, the creator of such a system is always in full control and can decide exactly which information the user will see during the creation of the system. Further, the methodology has been developed to support the user by only showing legal information, which further minimizes the risks. It provides an easy, safe and accessible way for the user to explore their legal rights.

ChatGPT, on the other hand, could also hypothetically be used to provide legal information. This would require less work, as the system may already have absorbed information in a certain legal area, which could be provided to the user. This way of providing legal information is also very flexible, as the system is able to carry out many different tasks, such as drafting documents or generating arguments. The user can interact with the system using their own words, in a natural way. However, the model may hallucinate certain parts of the answer. When used directly by laypeople, this approach could thus be risky. OpenAI specifically prohibits the use of its models to give legal advice directly to laypeople.

Now that we have understood the theoretical differences between ChatGPT and JusticeBot, an interesting follow-up is devising a few hypothetical cases, and comparing the answers given by the JusticeBot and ChatGPT, to empirically assess the differences. My colleague Tan Jinzhe has done such a study, which will be presented here in the following days.

Due to the different but complementary strengths of ChatGPT and JusticeBot, another fascinating research direction is exploring whether the strengths of both approaches can be combined. This could be done, for example, by using ChatGPT to support the creation of legal pathways in the JusticeBot methodology. Our team is exploring using pre-trained language models to summarize cases for inclusion in the JusticeBot[18] – ChatGPT and GPT-4 could prove to be a powerful extension of this project.

Likewise, ChatGPT may be used to facilitate the interaction of the user with the JusticeBot tool. The JusticeBot contains a structured representation of laws and legal information. This data could be exposed to ChatGPT. For example, a user may describe their situation, which can then be analyzed by ChatGPT in conjunction with the encoded data. Since the data is provided directly to the system, the issues with hallucinations are likely to be reduced. Of course, such a system would need to be evaluated in-depth before deployment to make sure that the provided information is not misleading in any way.

We are looking forward to performing this research, and will present more information about this approach in the coming days.

[1] Mark O’Neill, “How to Review and Refactor Code with GPT-4 (and ChatGPT)”, (29 March 2023), online: <https://www.sitepoint.com/refactor-code-gpt/>.

[2] Kristian, “How to Write a Great Story with GPT-4”, (30 March 2023), online: <https://www.allabtai.com/how-to-write-a-great-story-with-gpt-4/>.

[3] Taylor Soper, “Poet vs. chatbot: We gave the same prompt to a human, Microsoft Bing, and OpenAI’s new GPT-4”, (18 March 2023), online: GeekWire <https://www.geekwire.com/2023/chatbot-vs-poet-we-gave-the-same-poem-prompt-to-a-human-and-openais-new-gpt-4/>.

[4] Sandra Dawes-Chatha, “How to Use ChatGPT for Writing Difficult Emails at Work”, (10 March 2023), online: MUO <https://www.makeuseof.com/use-chatgpt-write-work-emails/>.

[5] Benjamin Marie, “Translate with ChatGPT”, (16 February 2023), online: Medium <https://towardsdatascience.com/translate-with-chatgpt-f85609996a7f>.

[6] “Check out this ShareGPT conversation”, online: <https://sharegpt.com/c/ICZsSl7>.

[7] OpenAI, GPT-4 Technical Report (arXiv, 2023) arXiv:2303.08774 [cs].

[8] “Introducing the new Bing”, online: <https://www.bing.com/new>.

[9] “An important next step on our AI journey”, (6 February 2023), online: Google <https://blog.google/technology/ai/bard-google-ai-search-updates/>.

[10] Drake Bennet, “ChatGPT Is an OK Law Student. Can It Be an OK Lawyer?”, (27 January 2023), online: Bloomberg.com <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2023-01-27/chatgpt-can-help-with-test-exams-it-may-even-offer-legal-advice>; Michelle Mohney, “How ChatGPT Could Impact Law and Legal Services Delivery”, (24 January 2023), online: Northwestern Engineering <https://www.mccormick.northwestern.edu/news/articles/2023/01/how-chatgpt-could-impact-law-and-legal-services-delivery/>.

[11] Long Ouyang et al, “Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback” (2022) arXiv, online: <http://arxiv.org/abs/2203.02155> arXiv:2203.02155 [cs].

[12] Tan Jinzhe, “An interview with ChatGPT: Using AI to understand AI”, (13 March 2023), online: Laboratoire de cyberjustice <https://www.cyberjustice.ca/en/2023/03/13/an-interview-with-chatgpt-using-ai-to-understand-ai/>.

[13] According to openai’s website (https://openai.com/pricing), the cost of gpt-3.5-turbo API is $0.0002/1K tokens, and the cheapest GPT-4 API cost is $0.03/1K tokens.

[14] “Global Economics Analyst The Potentially Large Effects of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth (BriggsKodnani)” (2023).

[15] Simon Willison, “Think of language models like ChatGPT as a ‘calculator for words’”, (2 April 2023), online: Simon Willison’s Weblog <https://simonwillison.net/2023/Apr/2/calculator-for-words/>.

[16] “Usage policies”, online: <https://openai.com/policies/usage-policies>.

[17] OpenAI, supra note 7.

[18] Olivier Salaün et al, “Conditional Abstractive Summarization of Court Decisions for Laymen and Insights from Human Evaluation” (2022) Legal Knowledge and Information Systems 123–132.

Ce contenu a été mis à jour le 14 décembre 2023 à 11 h 17 min.