The Future of ODR: Immersive technology enhancement and underlying technology evolution

By Jinzhe Tan, Research Assistant at the Cyberjustice Laboratory and PhD Student at Université de Montréal

1. Introduction

Advances in technology can bring new types of disputes and drive the development of new dispute resolution mechanisms. Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) mechanisms, which originated in the 1990s, has grown tremendously in the past few decades. People are becoming familiar with life on the Internet, and the cross-location and cross-time services brought by the Internet also bring cross-location and cross-time disputes. ODR has incomparable advantages in resolving such disputes, and such realistic needs have driven the emergence and development of ODR.

Although the concept of ODR is derived from ADR, the Internet-enabled ODR is no longer considered an online version of ADR but has characteristics that go beyond the original ADR: the term ODR is “proposed to offline dispute resolution mechanisms”. [1]

And after several decades of rapid Internet development, technological advances may once again give a huge boost to ODR technology, and existing new technologies may also bring new features to ODR.

In this blog, we will introduce two paths in the development of ODR technology, one is the progress of ODR occurrence field; the other is the update of ODR underlying technology. The former refers to helping users to interact better in the process of using ODR platform, such as making eye contact or even using body language to express themselves. The latter looks to revolutionize ODR from the bottom, building ODR technology on the blockchain so that it can win the trust of users in a decentralized form.

2. Advantages and Limitations of ODR

ODR technology has made a great contribution to the smooth resolution of disputes in the past decades. Compared with traditional offline dispute resolution methods, it is no longer restricted by physical location, and people can resolve disputes through the Internet across the barriers of distance and time, which can be said to bring great convenience to people for many cases with small subject matter.

Moreover, ODR is not limited by traditional legal procedures, and can switch between negotiation, mediation, arbitration, and appeals according to the willingness of the parties, which makes it easy to find the right solution for the dispute in the fastest way.

However, we can also find that ODR technology still has many disadvantages, such as the communication mode mainly based on asynchronous written communication,[2] which leads to the limitation of communication efficiency.

Although video and audio forms of communication became more familiar after the Covid-19 epidemic, video and audio can still lead to significant fatigue due to missing out of non-verbal communication.

At the same time, ODR technology also fails to fully solve the problem of trust, as the agreement reached by ODR is not directly legally enforceable and requires signatures from both parties, which also undermines the trust of ODR users in the system to some extent. According to Prof. Karim Benyekhlef and Prof. Nicolas Vermeys, ODR has not been able to find a suitable business model to motivate ODR service providers to provide sustainable services until today. [3]

3. Existing Technology Enhancement : Non-Verbal Communications in ODR

Like the exhaustion and confusion we experience in long Zoom or Teams meetings, video-based ODR can also cause people to communicate less efficiently. To solve this problem, scholars have tried to enhance existing technologies from different perspectives to improve the possibility of eye contact and body movements being perceived in ODR. The following are several existing directions of exploration, representing different ideas, and in the near future, these technologies may be used in practice.

3.1 Multi-screen and multi-camera system

In order to achieve the interaction effect in a real courtroom, some scholars propose to use a multi-screen and multi-camera system, where each participant’s picture will be captured by multiple cameras from different angles, and each group of screens and cameras can replace one participant respectively, so when a participant turns his head to look at one of the screens, it is equivalent to making eye contact with a specific person shown in the screen. This mode can partially restore eye contact in a real courtroom.

3.2 Curved screen and eye tracking camera system

This system is a simplified version of the multi-screen multi-camera system, using a curved screen instead of multiple displays at different angles, and an eye-tracking camera instead of a multi-camera system. This system can provide a multi-angle view and partially simulate eye contact while saving cost.

3.3 Dispute Resolution Meta-Universe

In this model, a Unity or Unreal game engine is used to build a courtroom directly in the virtual space, and each dispute participant can get an avatar in the virtual space. In this system, participants can look in different directions at will, as in a real courtroom, or interrupt each other at any time, or even use body language to express their thoughts. Although this model can restore non-verbal communications in the real courtroom to the greatest extent, such a model requires very high network bandwidth and at least 12 cameras, which is quite demanding for the construction of the virtual courtroom.

4. Decentralized Justice: Blockchain-Based Dispute Resolution

4.1 Decentralized Justice

The concept of decentralized justice was introduced to address the issues of trust and profitability models. Since many ODR platforms are developed by private companies, agreements reached through the platform are not enforceable, and only if all parties sign the agreement, the agreement can be enforced in the prior legal system. In contrast, a decentralized justice model based on blockchain and smart contracts can enable automatic enforcement of contracts. Just like ODR was initially proposed to solve specific problems in e-commerce, but was subsequently applied to other areas, BDR started as a new tool for tech companies to resolve disputes on the blockchain, but was soon applied to traditional disputes.

ppp

4.2 Blockchain-Based Dispute Resolution

Starting from 2017, several distributed dispute resolution mechanism platforms were established. And there are three main existing mainstream distributed dispute resolution platforms: [4]Kleros, Aragon and Jur.

The founders of the Kleros mechanism first used “Blockchain-Based Dispute Resolution (BDR)” in their white paper, which has the following characteristics: [5]

- “Decentralization” of the dispute resolution system

- “Coding” the basis for dispute resolution

- “Automation” of dispute resolution execution

After the Kleros mechanism appeared on Ethereum, more than a dozen more companies released blockchain-based dispute resolutions one after another. Until today, some of the older BDR platforms have been shut down, such as Sagewise, the originator of the important concept of the BDR ecosystem. [6]

According to Kleros’ description of itself, it uses the game theory concept of Schelling Points, and uses blockchain and crowdsourcing technology to adjudicate disputes. The main logic of its operation is to use tokens to reward jurors who reach a verdict in line with others and to punish jurors who fail to do so, thus providing jurors an incentive to vote honestly through analysis of the evidence.

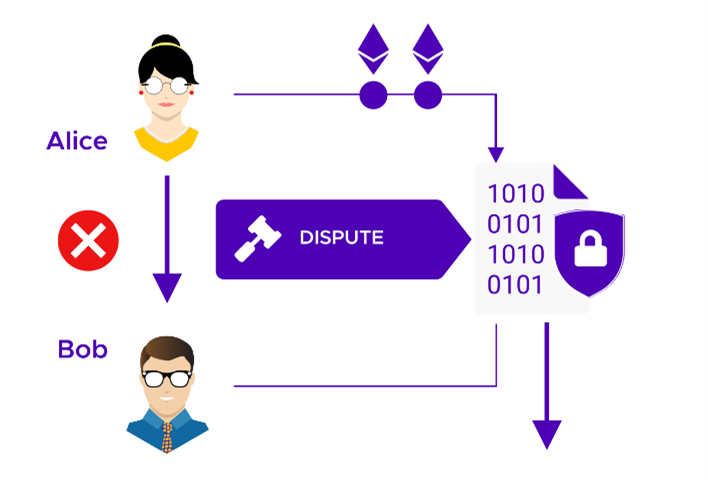

We will use Kleros as an example to illustrate how BDR works. As shown in the figure below, a smart contract is established between two disputing parties, which will automatically initiate a dispute resolution mechanism after a dispute arises, and the Kleros smart contract automatically draws a defined number of jurors.

Figure 1:Kelros’ operating mechanism

Source:https://blog.kleros.io/become-a-juror-blockchain-dispute-resolution-on-ethereum/

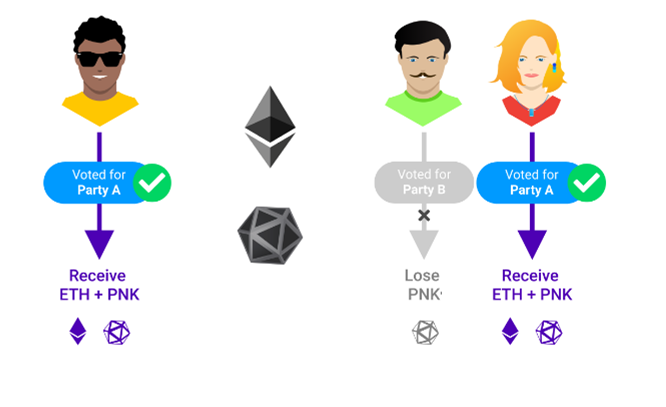

After the jury is empanelled, the jurors will review the evidence and facts and make their own judgments, and jurors who vote consistently will be rewarded and penalized for the opposite.

Figure 2: Jurors who vote consistently will be rewarded and penalized for the opposite

Source:https://blog.kleros.io/become-a-juror-blockchain-dispute-resolution-on-ethereum/

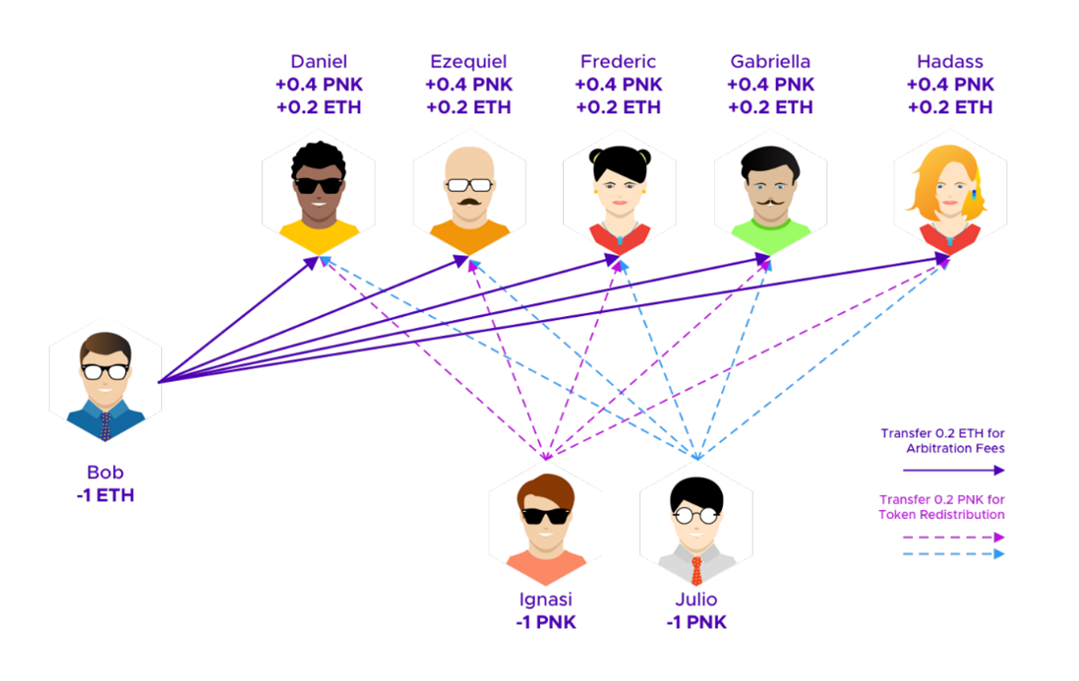

Token redistribution after the vote with seven jurors. Tokens are redistributed from jurors who voted incoherently to jurors who voted coherently. Bob lost the dispute and pays the arbitration fees. The other deposits are refunded.[7]

Figure 3: The way tokens are distributed

Source: https://kleros.io/whitepaper.pdf

As can be seen from the above, the dispute resolution logic of decentralized justice is different from previous models. It primarily uses incentives to facilitate fair verdicts by juries, rather than relying on the morality of the jury. With this comes a shift in the jury’s goal from one of “rendering an ethical and just verdict” to one of “rendering a verdict consistent with others”, which can cause distortions in the final outcome.

We can use an example to illustrate, suppose that multiple jurors need to choose a number from a series of numbers, those who choose the number with the most selection will be rewarded, while the opposite is penalized: 2350, 2890, 3482, 4039, 5083, 1726, 1000, 1982, 1928. Predictably, jurors will choose a number that seems more likely to be chosen in order to increase the probability of receiving a reward: 1000. [8] But the logic behind this thinking is not consistent with the ethical norms of traditional dispute resolution.

This leaves us with many unanswered questions: How should such a misalignment of incentives be addressed? With such misaligned incentives, what is the likelihood that jurors will return an unjust verdict?

5. Conclusion

Advances in technology are always two-sided, enhancements to non-verbal communications mean higher equipment costs and internet costs. While decentralized justice partially solves the problems of ODR, it also brings new problems, how to drive the technology in the right direction remains a challenge for scholars and practitioners.

As Werbach said in 2019, “it’s too early to

call blockchain a revolution”, this is a statement that may still be true in

2022, but it remains to be seen whether blockchain will evolve into a

revolution in the future.

[1] Thomas Schultz, “An Essay on the Role of Government for ODR: Theoretical Considerations about the Future of ODR” (2003) Online Dispute Resolution (ODR): Technology as the “Fourth Party” at 5.

[2] Orna Rabinovich-Einy, “The Past, Present, and Future of Online Dispute Resolution” (2021) 74:1 Current Legal Problems 125–148 at 140.

[3] Mohamed S Abdel Wahab, M Ethan Katsh, & Daniel Rainey, Online dispute resolution: theory and practice: a treatise on technology and dispute resolution, Second Edition (Eleven International Publishing, 2021) at 591.

[4] Yann Aouidef, Federico Ast & Bruno Deffains, “Decentralized Justice: A Comparative Analysis of Blockchain Online Dispute Resolution Projects” (2021) 4 Frontiers in Blockchain, online: <https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbloc.2021.564551> at 3.

[5] Kevin Werbach, The blockchain and the new architecture of trust (Mit Press, 2018) at 91.

[6] Cemre Kadioglu Kumtepe, A Brief Introduction to Blockchain Dispute Resolution (Rochester, NY, 2020) at 143.

[7] Clément Lesaege, Federico Ast & William George, “Kleros Short Paper v1. 0.7” (2019) Kleros, septiembre de at 8.

[8] Thomas C Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict: with a new Preface by the Author (Harvard university press, 1980).

Ce contenu a été mis à jour le 21 février 2023 à 11 h 38 min.